HELLEVIK

Come posso essere nato nell’iowa, a duemila miglia dal mare, quando i miei antenati erano tutti pescatori e vichinghi sul baltico? Ovviamente ho trovato l’acqua, ho trovato l’acqua nel lago michigan, a sole trecento miglia da casa, ma non sapevo bene che la maggior parte dei miei antenati paterni erano morti in mare quando ho quasi perso la vita sul lago michigan, tutta la notte sul canotto, guardando i miei amici morire e sentendo la vita che lentamente abbandonava il mio corpo. Non sono affondato durante una tempesta come i miei antenati, mi sono gelato fino a morire, quasi fino a morire, e ora affronto le calme acque grigie del baltico chiedendomi cosa mi abbia riportato indietro, qui, alle tombe d’acqua dei miei antenati, il mare che somiglia tanto al lago Michigan. Così calmo e quieto in una giornata primaverile con un sole caldo, le bandiere che sventolano nella brezza, l’erba marrone che diventa verde lungo la riva, una nave da carico grigia all’orizzonte, gabbiani che gracchiano in alto, e giù, sul fondo sabbioso, le barche e le ossa dei miei antenati fin dall’età della pietra. Son tornato a casa finalmente?

I miei antenati schneller erano gente che viveva sui carri, zingari bianchi che dovevano viaggiare, che non morivano mai dov’erano nati. Ed ora eccomi in un villaggio da cui la gente non va via da 10,000 anni, o forse più, tranne che per pescare o per combattere ma per poi tornare sempre, per morire dove è nata. Navi grigie all’orizzonte grigio, pescatori barbuti che annegano in un mare freddo e senza cuore, generazione dopo generazione a coprire il fondo sabbioso. Non c’è da meravigliarsi se i cimiteri sono così piccoli, pochi uomini ci sono seppelliti. Il mare è il nostro cimitero, come il lago michigan è quasi stato il mio. Era nei geni, nel sangue, il mio destino? Sono stato salvato dal lago michigan in modo da poter vedere il vero cimitero dei miei antenati, il mar baltico? Quell’isola di sabbia è lontana dalla riva, coperta dalla boscaglia, la nostra lapide? O sono i moli di pietra le nostre lapidi, o sono le asciutte mura di pietra attorno alle nostre case, le nostre lapidi? O gli enormi macigni ancora lasciati nei campi? La pietra e tutt’attorno, pietra e acqua del colore della pietra, fredda come la pietra. La fredda e grigia costa. Le abbiamo dato la vita, il nostro sangue, il nostro sperma. Le nostre ossa.

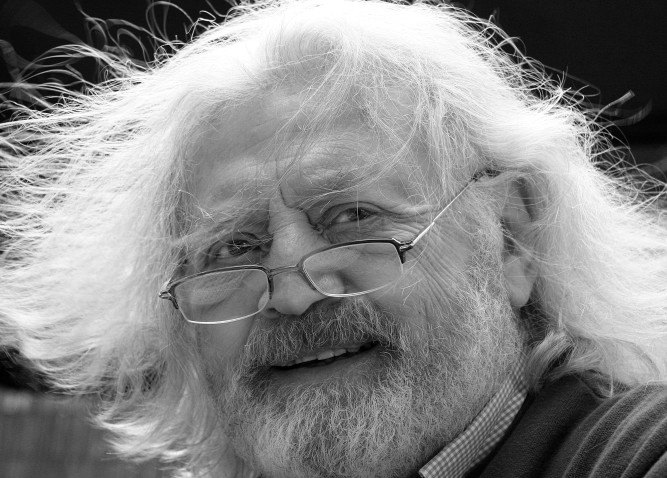

Paul Polansky, poeta, fotografo, operatore culturale e sociale, è diventato negli anni un personaggio importante per il suo impegno a favore delle popolazioni Rom, dei poveri, degli emarginati.

Guardi nelle piccole case che punteggiano la baia e cosa vedi?fiori su ogni davanzale. Luminosi fiori gialli come raggi di sole, fiori su ogni finestra. Ogni finestra che si affaccia sul mare ha fiori. Non possono mettere i fiori sulle tombe marine dei loro uomini, ma possono mettere i loro fiori alle finestre, le finestre che riflettono la luce del mare, le ombre delle nostre anime. Dal 1730 ad oggi oltre 600 pescatori si sono persi in mare da un villaggio che non ha mai avuto più di duecento anime finché la gente dalla terraferma non ha iniziato a costruirci case per il week end. Ogni famiglia ha una foto che mostra tre generazioni di vedove. Son sicuro che è lo stesso per le vecchie famiglie di minatori; anche noi eravamo minatori, minatori del mare o loro erano pescatori delle miniere?minatori e pescatori condannati a morire sotto la superficie.

Com’è bello vedere una nave che arriva in porto, torna a casa, fino a quando non vedi la bandiera a mezz’asta e il pescato scaricato sull’antico molo di pietra non è salmone, passera nera o aringa, ma il grigio corpo affumicato di un altro pescatore che non ha fiutato la tempesta davanti alla prua. Ero privo di sensi quando hanno scaricato i corpi di danny e tony. Il mio non deve essere stato molto diverso, tranne per il fatto che ero probabilmente avvolto in coperte perché cercavano di trattenere in me l’ultimo calore di vita.

Una donna zappa il suo orto di verdure sapendo di poter dar da mangiare qualcosa alla famiglia se il marito non ritorna dal mare. Foglie verdi invece di squame argentate. Ma suo figlio andrà ancora in mare o emigrerà. In ogni caso, presto o tardi lei non lo rivedrà più. Ma dall’america lui potrà mandare una foto quando si sposa, dal fondo del mare non potrà mandare nulla.

Perché le madri vivono così a lungo sull’isola, perché sono punite così a lungo per le morti dei loro padri, mariti, figli? Tutti gli uomini muoiono intorno ai quarant’anni, mentre tutte le donne vivono fino ai novanta. Perché dio ha organizzato tutto così?cosa sta cercando di dire? Se lasciate che i vostri uomini vadano in mare vi lascerò in vita per due generazioni in più? Portateli via dal mare, il mare è mio!

Un cigno dal collo lungo sbatte le ali proprio sopra l’acqua. raramente Il mare lo prende, si prende solo gli uomini, i pescatori del nostro villaggio. I gabbiani ridono quando andiamo in mare. Mentre le donne piangono. Il mare sembra così calmo prima di diventare pericoloso. Anche sul lago michigan in un caldo giorno di luglio ci divertivamo. Il mare era divertente finché il sole non tramontò. Allora le onde non ci fecero più sentire sulle montagne russe, ma si infransero sui nostri freddi corpi nudi, gelandoci a morte. Come un pomeriggio piacevole può trasformarsi

in una serata d’inferno, in una notte di dannazione. Non sono nato sul mare ma i miei geni si, e ora ho trovato i morti. Sono tornato a casa, e so dove morirò, dove sarò sepolto, senza lapide, ma sulla finestra ci saranno fiori e forse un giorno all’anno una candela per ricordarci.

Traduzione di Valentina Confido

Foto di Salvatore Marrazzo

HELLEVIK

how could i be born in iowa, two thousand miles from the sea when my ancestors were all fisherman and vikings on the baltic? of course i found the water, i found the water at lake michigan, only three hundred miles from home, but little did i know that most of my paternal ancestors had died at sea when i almost lost my life on lake michigan, all night in the rubber raft, watching my friends die, feeling my life slowing leaving my body. i didn’t drown like my ancestors in a storm, i just froze to death, almost to death, and now i’m facing the calm gray waters of the baltic wondering what brought me back, here, to the watery graves of my ancestors, the sea that looks so much like lake michigan. so calm and peaceful on a spring day with a warm sun, the flags fluttering in the breeze, the brown grass turning green alongside the shore, a gray freighter on the horizon, squawking sea gulls overhead, and below on the sandy bottom the boats and bones of my ancestors since the stone age. have i come home at last?

my schnellers were wagon folk, white gypsies who had to travel, never dying where they were born. so here i am in a village where the people have not left for 10,000 years, maybe more, except to fish and fight but always to return, to die where they were born. gray ships on a gray horizon, bearded fishermen drowning in a cold heartless sea, generation after generation covering the sandy bottom. no wonder the graveyards are so small, so few men are buried there. the sea is our cemetery, as lake michigan was almost mine. was that in the genes, in the blood, my destiny? was i saved from lake michigan so i could see the real cemetery of my ancestors, the baltic sea? is that sandy island off shore, covered in scrub, our tombstone? or are the stone piers our tombstones, or the dry stone walls around our houses our tombstones? or the huge boulders still left in the fields? stone is all around, stone and water the color of stone, cold as stone. the cold gray coast. we gave it life, our blood, our sperm. our bones.

look in the small houses that dot the coves and what do you see? flowers on every window ledge. bright yellow flowers like the suns rays, flowers in every window.

every window that looks out to sea has flowers. they cant put the flowers on their men’s sea graves, but they can put their flowers in the windows, the windows which reflect the light of the sea, the shadows of our souls. from 1730 until today over 600 fishermen have been lost at sea from a village that never had more than two hundred souls until the people from the mainland started building weekend homes. every family has a photo showing three generations of widows. i’m sure it’s the same in the old mining families; we were miners too, miners of the sea or were they the fishermen of the mines? miners and fishermen condemned to die beneath the surface.

how beautiful to see a ship sailing into harbor, coming home, until you see the flag at half mast and the catch unloaded on the ancient stone pier is not salmon, flounder or herring, but the gray bloated body of another fishermen who didn’t smell the storm off his bow. i was unconscious when they unloaded the bodies of danny and tony. mine couldn’t have looked any different, except i was probably wrapped in blankets as they tried to keep the last warmth of life in me.

a woman hoes her vegetable garden knowing she can fed her family something if her husband doesn’t return from the sea. green leaves instead of silver scales. but her son will still go to sea or emigrate. whatever, sooner or later she will never see him again. but from america he can send a photo when he gets married, from the sea bottom he can send nothing.

why do mothers live so long on the island, why are they punished so long for the deaths of their fathers, husbands, sons? all the men die in their forties, while all the women live into their nineties. why has god planned it this way? what is he trying to tell them? if you let your men go to sea I will make you live for two more generations? take them away from the sea, the sea is mine!

a long necked swan flaps her wings just above the water. the sea seldom takes her, only men, the fishermen of our village. the sea gulls laugh as we go to sea. while the women cry. the sea looks so calm before it becomes treacherous. even on lake michigan on a warm july day it was fun. the sea was fun until the sun went down. then the waves were no longer giving us a roller coaster ride, but crashed over our cold naked bodies, freezing us to death. how an afternoon’s pleasure can change

into an evening of hell, a night of damnation. i wasn’t born on the sea but my genes were and now i’ve found the dead. i’ve come back home, and i know where i will die, where i will be buried, without a tombstone, but in the window there will be flowers and maybe one day of the year a candle to remember us by.

Acquista il libro

Lascia un commento